1945-1947: Mach Buster

By Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Dr. James Young, Chief Historian

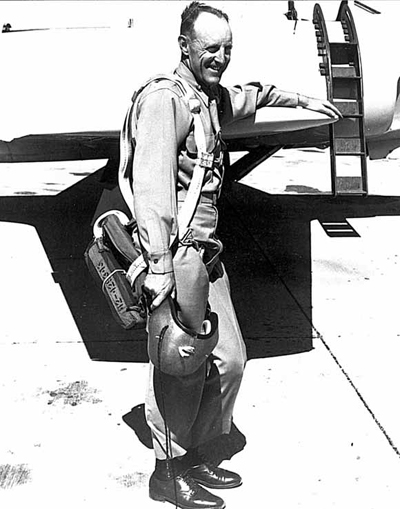

After a short stint as a flight instructor at Perrin Field, TX, Yeager was assigned as assistant maintenance officer in the Fighter Section of the Flight Test Division at Wright Field, OH. He was at the right place, at the right time. Wright Field was the center of Army Air Forces R and D and, since it was his job to check out all aircraft coming out of maintenance, he got to fly almost every fighter on the flight line. He demonstrated such exceptional skill that he was selected to fly in air shows and, in September 1945, he made his first trip to Muroc Army Air Field (now Edwards AFB) where he flew accelerated service trials on the new P-80A Shooting Star, America’s first operational jet fighter.

Yeager in the cockpit of a P-80A at Wright Field (note his headgear, the crown of a tank corpsman’s helmet snapped onto his original leather flying cap).

The P-47D was one of the first aircraft Yeager checked out in after arriving at Wright Field.

Considered the father of modern Air Force flight test, Col Albert Boyd was chief of the Flight Test Division. Tough and absolutely unyielding in his standards, he was trying to build a cadre of test pilots that could set industry-wide standards for the profession. Under his scrutiny, only the very best pilots were selected to enter the new test pilot school at Wright Field. After closely observing and flying with Yeager, Boyd handpicked him for the school in January 1946.

Col Albert Boyd, chief of the Flight Test Division at Wright Field, would subsequently serve as the first commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB.

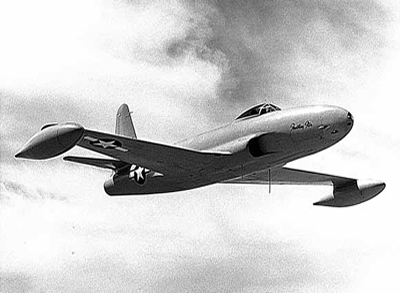

New P-80As on the ramp during accelerated service trials at Muroc Army Air Field, October 1945.

A new P-80A Shooting Star in test over Muroc Army Air Field, October 1945.

With only a high school education, he was challenged by the advanced academics but managed to graduate.“Because of my flying ability,” he later explained “they took mercy on my academics.” In June 1947 Colonel Boyd made one of the most important decisions of his career when he chose one of his most junior test pilots to attempt to become the first person to exceed the speed of sound in the rocket-powered Bell XS-1. He chose Yeager because he considered him the best “instinctive” pilot he had ever seen and he had demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to remain calm and focused in stressful situations. The X-1 program certainly promised to be stressful; many experts believed the so-called “sound barrier” was impenetrable. Yeager and the rest of the small Air Force test team met at Muroc in late July.

After three glide flights in the Bell XS-1 rocket research plane which he named Glamorous Glennis, he flew it to a speed of 0.85 Mach on his first powered flight on 29 August. He encountered severe buffeting and sudden nose-up and -down trim changes during his next six flights. Then, during his eighth flight on 10 Oct., he lost pitch control altogether, as a shock wave formed along the hingeline of the X-1 elevator. He reached Mach 0.997 but without pitch control it would have been foolhardy to proceed. The X-1 had been designed with a moving horizontal tail and Capt Jack Ridley convinced Yeager that by changing its angle of incidence in small increments, he could control the craft without having to rely on the elevator. This had never been attempted at extremely high speeds but Yeager was game to give it a try on the next flight.

Ground test of the X-1’s power plant. The airplane was powered by a 4-chamber, 6,000-lb thrust XLR-11 rocket engine.

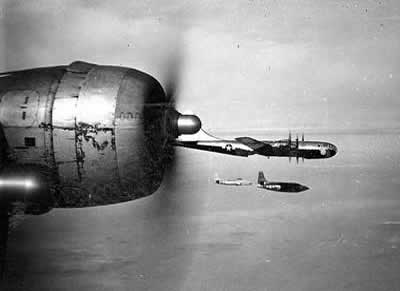

Famous photo shot by Bob Hoover from his FP-80 chase plane as Yeager and the X-1 accelerated past him on 14 October 1947.

On 14 Oct. he dropped away from the B-29, fired all four chambers of his engine in rapid sequence and bolted away from the launch aircraft. Accelerating upward, he shut down two chambers and tested the moveable tail as his Machmeter registered numbers of 0.83, .88 and 0.92. Moved in small increments, it provided effective control. He reached an indicated Mach number of 0.92 as he leveled out at 42,000 feet and relit a third chamber of his engine. The X-1 Glamorous Glennis rapidly accelerated to 0.98 Mach and then, at 43,000 feet, the needle on his Machmeter jumped off the scale.

Chuck Yeager had just crossed the invisible threshold to flight faster than the speed of sound. He attained a top speed of Mach 1.06 (700 mph). When Yeager’s achievement was finally declassified in June of 1948, he was quickly accorded celebrity status as “The Fastest Man Alive,” and was awarded the most prestigious honors in aviation. The words accompanying the Collier Trophy aptly summarized the magnitude of his flight: “This is an epochal achievement in the history of world aviation–the greatest since the first successful flight of the original Wright Brothers’ airplane, forty-five years ago.”

Yeager, standing on lift device that descended from the bomb bay of the B-29, just prior to entering the X-1’s cockpit.

In 1948, retired Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces Henry H. “Hap” Arnold (in sunglasses) met Yeager on the lakebed for a briefing on his flights in the X-1.

Dates of the 8 Air Force powered flights leading up to breaking the sound barrier

- 1st powered flight: 29 Aug 1947

- 2nd powered flight: 4 Sep 1947

- 3rd powered flight: 8 Sep 1947

- 4th powered flight: 10 Sep 1947

- 5th powered flight: 12 Sep 1947

- 6th powered flight: 5 Oct 1947

- 7th powered flight: 8 Oct 1947

- 8th powered flight: 10 Oct 1947

Bell X-1 Report

Yeager’s pilot report for his 14 October 1947 flight in the X-1. All Mach numbers were presented as “Machi” which meant they were the “indicated” Mach number readings from Yeager’s Mach meter and not necessarily his “true” airspeed at any point in time. Flight instruments of that era were subject to “lag.” Thus, while the Mach meter indicated Mach 0.92, the aircraft could actually be moving at a speed of 0.94 or 0.95 Mach.

Postflight on the lakebed – Yeager and the X-1.

An extremely rare photo of the X-1 just after release from the B-29 Launch aircraft.

Punching a Hole in the Sky

By Shannon White

After Chuck spent one of the low points of his career teaching cadets to fly at Perrin Field, fate intervened on his behalf. A new Air Corps rule said that anyone who had evaded capture during the war could transfer to the base of his choice.Glennis was expecting their first child, and the couple decided it would be wise to be near Hamlin where Chuck’s mother could lend a hand. He got out a map and determined that the nearest base was Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. Little did he know how big an impact would result from that simple decision.

Because he had been a maintenance officer and crew chief as well as a pilot, Chuck was assigned as Assistant Maintenance Officer in the Fighter Test Section at Wright Field. His duties consisted of flying each aircraft that had undergone maintenance to ensure all the systems worked. This meant no shortage of flying and a seemingly endless array of new planes, including the jet aircraft that were just starting to make their way onto the flight line. The Flight Test Commander, Colonel Albert Boyd, was a strict disciplinarian and accomplished pilot who demanded the best from his personnel. Boyd took notice of Chuck’s abilities in the cockpit and was impressed by the young Captain’s knowledge of each aircraft’s mechanical systems. In the fall of 1945, Boyd and a group of test pilots headed to Muroc Air Base in the Mojave Desert of southern California for tests on the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, the plane that would become America’s first operational jet fighter. Accompanying Boyd and the group was Maintenance Officer Yeager.

It was on that trip that Boyd validated his trust in Chuck’s talents. The Colonel selected Chuck over the regular test pilots to ferry one of the unpredictable jets back to Wright Field. Soon, the Colonel asked if Chuck had any interest in attending test pilot school.

Chuck had reservations about his lack of education, but he and Colonel Boyd both knew he could out-fly any pilot at Wright Field. While at test pilot school, Chuck befriended a flight engineer named Jack Ridley. Jack’s talent for explaining the complex rules of mathematics and physics in a way Chuck could understand drew the two together. They would join another friend of Chuck’s and fellow pilot at Wright Field, Bob Hoover, on a project that would change all of their lives – the world of and aviation – forever.

Supported by a team from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the Air Force X-1 test team included, from l-r: Lt Ed Swindell (B-29 flight engineer); Lt Bob Hoover (X-1 backup and chase pilot); Maj Bob Cardenas (B-29 launch pilot); Yeager; Dick Frost (Bell X-1 project engineer and chase pilot); Capt Jackie Ridley (Air Force project engineer).

Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt Vandenberg presented Yeager with the McKay Trophy for 1947 (awarded each year for the most meritorious flight by an Air Force individual, team or unit).

Muroc Air Base was the perfect place for testing aircraft. The weather was good year-round and there were hundreds of miles of nothing but desert and dry lakebeds – nature’s perfect runways.

It was here that the Bell Aircraft Company was testing a radical new aircraft designed to go faster than anything before it. Bell wanted its airplane and its civilian test pilot to be the first to exceed the speed of sound. The X-1 had been built for just that purpose.

Since the days of aerial combat in WWII, pilots had experienced unstable controls and terrific structural mishaps when their aircraft reached speeds approaching the speed of sound. It was theorized by many engineers that a physical barrier existed that would prevent flight beyond Mach 1. Yet an argument remained that there were things that flew faster than sound, like bullets.

Bell Aircraft started with the shape of a .50-caliber bullet and designed the X-1 to try and break the so-called “sound barrier.” The small plane was powered by four powerful rocket engines and was structurally very sound. It was built to withstand 18 times the force of gravity. Bell was testing the aircraft at Muroc in early 1947 when a disagreement with their pilot, Chalmers “Slick” Goodlin, caused the Air Corps to take notice.

Goodlin demanded huge amounts of bonus money for taking the aircraft though Mach 1and Bell had put the project on hold while they tried to resolve the issue. Meanwhile, Colonel Boyd saw the tremendous potential such a program would have on the future of the Air Corps. He successfully lobbied to get the entire X-1 program under his command and began a search for an experienced test pilot who would not shirk from the risks involved.

Chuck threw his name in the hat, but figured his lack of education would prevent him from being selected. Colonel Boyd, on the other hand, was well aware of Chuck’s abilities in the cockpit and his interest in learning everything he possibly could about every airplane he flew. That kind of interest and motivation, coupled with a damned good pilot who could stay focused under pressure, was what Boyd was looking for. He found the perfect combination in Chuck Yeager.

Bob Hoover was selected as backup pilot and Jack Ridley as flight engineer for the X-1 project. The men arrived at Muroc to begin chipping away at the sound barrier in July 1947.

The program was different than anything Chuck had ever done before. The X-1 did not take off from the ground but instead was carried aloft in the bomb bay of a modified B-29 Superfortress. When the B-29 reached altitude, Chuck climbed out into the bomb bay and through the X-1’s tiny side door. The door was locked into place and the X-1 was dropped free of the B-29. Once in free flight, the X-1’s rocket engines were fired. The plane carried only a few minutes’ worth of fuel (a mixture of liquid oxygen and alcohol), then Chuck would glide back to earth and land at Roger Dry Lake.

Chuck’s first few flights were non-powered in order to give him a feel for the handling characteristics of the X-1. By August, the team was ready.

The X-1s first powered flight with Chuck at the controls was on 29 August, 1947. Chuck was thrilled with the aircraft’s performance. He realized in that one flight that, although he would certainly have to be careful, the sound barrier didn’t stand a chance.

The X-1 team followed a strict set of orders from Colonel Boyd about how to proceed with the program. Each flight was to only increase in speed by two hundredths of a Mach number. Taking time with the program, analyzing the data from each flight and deciding how to proceed was the safest way to progress. Chuck was confident about the airplane’s capabilities and the flights progressed into the fall.

The sixth powered flight took place on 5 October. Chuck experienced turbulence and buffeting from shock wave compression for the first time as he reached .86 Mach on that flight. The next flight brought him face-to-face with an unknown phenomenon that would become the biggest result to come from the entire program.

On his seventh powered flight, Chuck had the X-1 at .94 Mach when his controls suddenly ceased to function. Shock waves on the plane’s control surfaces made operation impossible. Always cool-headed in such situations, Chuck turned off the plane’s rockets to slow down and jettisoned the remaining fuel. He glided back in to the lakebed and explained to Ridley what had happened. Engineers had predicted that as the plane reached the speed of sound, its nose would pitch up or down. At .94 Mach, however, Chuck had lost the ability to operate the plane’s elevator. Without it, he could not correct for whatever pitch change might occur at Mach 1. It was Jack Ridley who came up with the solution.

Ridley believed it was possible for Chuck to control the aircraft using the horizontal stabilizer. Bell had built the capability into the X-1 of controlling the stabilizer’s angle of attack. Chuck and Jack Ridley gave it a thorough testing on the ground, then told Colonel Boyd they felt confident trying the method in flight.

The eighth powered flight followed the same plan as the one before. Chuck tested the horizontal stabilizer control at .96 Mach and Ridley was right. The system worked and Chuck was able to regain control of the X-1. The next flight would come after the weekend, and plans called for taking the X-1 out to .98 Mach.

Chuck and Glennis had dinner at Pancho’s, a favorite watering hole for Muroc pilots, on 12 October. After dinner, they decided to take a couple of Pancho’s horses for a ride. As they raced back to the barn, neither of them realized the gate had been closed. Chuck’s horse hit the gate and threw him off. That landing was one of his roughest; he broke two ribs when he hit the ground.

He knew Colonel Boyd would never allow him to fly with broken ribs, but Chuck wasn’t about to let the injury keep him out of the cockpit. Glennis drove him to a doctor off base who taped up his ribs. Chuck knew he could fly with his ribs broken, but he wasn’t sure how to close and latch the X-1’s side door which had to be pulled into place and then latched from the inside. He said as much to Ridley, who fashioned a makeshift handle out of a broomstick. Chuck tried it out in the X-1 on the ground and it worked perfectly. He used the stick to push the lever and lock the cockpit door.

The morning of 14 October saw the X-1 team ready for another flight. Plans called for Chuck to reach about .98 Mach. Everything proceeded as planned. Chuck latched the door with the broomstick and settled in. At .94 Mach, he corrected for the plane’s instability using the horizontal stabilizer trim switch. With fuel remaining, he fired another of the X-1’s rockets and watched the Mach meter.

At .965 Mach, the meter fluctuated and went off the scale. The ground control operators simultaneously reported they heard what they thought was thunder in the distance. In fact, they had heard the first sonic boom ever produced on earth. When the Mach needle registered off the scale, Chuck noticed that the X-1 no longer buffeted; supersonic flight was as smooth as could be. He left the airplane in this newly entered realm for about 20 seconds, then turned off two of the four rocket chambers and decelerated back to subsonic speeds.

The flight was, relatively speaking, pretty uneventful. Chuck would later say his ride through the sonic wall was nothing more than a poke through Jell-O. Still, Chuck and the rest of the X-1 team knew on 14 October that they had done what they came to the high desert to do.

Chuck Yeager punched a hole in the sky that day.

Yeager with the Collier Trophy on display in the Flight Test Division at Wright Field.

President Harry S. Truman presented the Collier Trophy to the NACA’s John Stack (left), Yeager, and Larry Bell (right) for the greatest achievement in aeronautics in 1947.